Umami the 5th Taste

You may have heard this word here in the Western world too recently. It first started to appear in technical fields, such as sommelier and tasting classes. Then it gradually became common in popular articles and TV programme about cooking and food products. “Umami” is a Japanese word that literally means “good taste”.

The Japanese language allows you to write the same word in different ways. You can write the world umami as in the picture, with the two ideograms of good (旨) and taste (味) together. Or you can use two phonetic characters for the first part (“good”), and one ideogram for just the word “taste” (うま味).

In fact, the real meaning of the word “umami” is different from “good” referring to food, for which the Japanese use the word “oishii” (美味しい) instead.

Umami: the Fith Taste

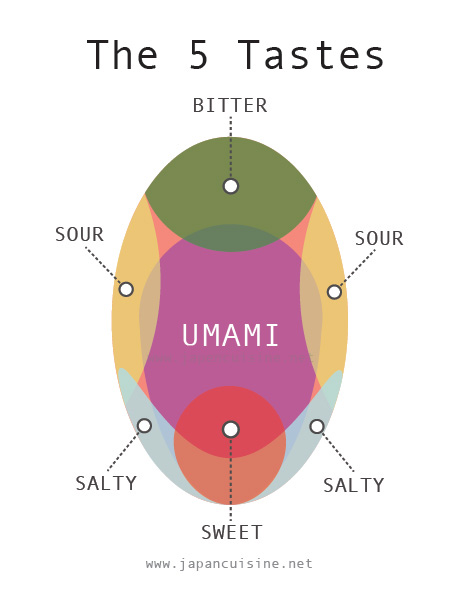

In the West we often define umami as the fifth taste. That is because it is not possible to fit it in one of the 4 basic tastes that the human tongue perceives: sweet, salty, sour, bitter.

Some research conducted on volunteers seems to show how we perceive umami at the centre of the tongue. Researches gave the volunteers umami reach food to eat, and asked them to locate the sensation on their tongue. More recent studies seem to disprove the old schemes like the one above, which divide the tongue into well-defined areas dedicated to the perception of individual tastes. The receptors of the various tastes are spread throughout the mouth, with a slight concentration in some areas of the tongue. There is also a strong component of subjectivity in the localization of taste sensations.

Anyhow some respondents associated umami with saltiness. Others perceived it at the bottom of the tongue, especially after swallowing. Most of the interviewed defined it as a general increase in taste perceptions in the whole mouth. And that is not just by accident.

Flavor enhancer

In Japan, the umami principle has been identified and isolated. It is the infamous monosodium glutamate, or sodium salt of glutamic acid to call it by its scientific name. Japanese chemist Professor Kikunae Ikeda discovered it in 1908 inside kombu (Laminaria Japonica).

Kombu is a ribbon-shaped seaweed, about twenty centimetres wide and several metres long. It is collected in the sea, dried and cut into strips. It is one of the basic ingredients of Japanese cuisine, used precisely to flavor broths, rice, sauces and various gravies. A piece of dry kombu about 10-15 centimeters is soaked in the water that will be used to make the basic broth of miso soup, nabe or to cook rice.

Some time ago it became famous in the West because of a miraculous diet based on its infusion, the kombucha.

Sodium Glutamate

Once they discovered the compound in kombu, they soon found ways to synthetise it with an industrial process. Today sodium glutamate is on the shelves of any Japanese food store.

Many foreigners that just moved to Japan know this. When they go shopping, as they cannot read product labels, they often mistake bottles of sodium glutamate for cooking salt. The effects when they first use it are quite funny.

Monosodium glutamate is an amino acid, one of the components of protein. It is precisely foods rich in protein and free amino acids that have the most umami.

Besides kombu there are many other ingredients of Japanese cuisine used for their ability to increase the umami of a recipe. The soy sauce itself is in many ways a flavor enhancer. Shiitake mushrooms, katsuo (which together with kombu is essential in the preparation of the broth for miso-shiru), nori, dried sardines and scallops. These are all ingredients that in traditional markets and luxurious Japanese department stores, have a dedicated corner, that of dashi, the basic broth.

Umami VS Sapidity

Lately we’ve been hearing a lot about umami in enthusiastic tones that betray a certain xenomania. Many superstar chefs boast of using it together with katsuo to prepare their elaborate dishes.

They also said that there has never been a full awareness of umami in Western cuisine. And this would justify the use of the foreign word.

In fact, not only English has a specific term to refer to what the Japanese call umami, but certain ingredients have always been used because of their ability to naturally enhance the flavor of a recipe.

The English term is “sapid“. Which is something quite different from “salty”.

Sherry is often used as a cooking wine because it gives a sapid texture to the food. In Italian cuisine parmesan cheese, dried porcini mushrooms and tomato sauce are all ingredients rich in free amino acids. They are used to increase that particular sapid flavor that the Japanese call umami.

Considering the millionaire interests of the food additives business, there are doubts about the genuineness of this sudden fashion of umami.

We may suspect that all this pro-umami campaign serves to exploit the popularity and “glamour” of Japanese cuisine to improve the image of sodium glutamate, an omnipresent food additive, tarnished by recent controversial studies on its effects on health.